June 2, 2023, Shenzhen – The world’s largest ever study of primates has been published by a collaboration of scientists from multiple countries including China, the U.S., Denmark, Spain, Germany, the UK, Canada, Japan, and India. By carrying out comparative research on the genome data of 50 species of primates from 14 families and 38 genera, the study yields a profound understanding of the evolutionary process of primates, marking a significant advancement in scientific knowledge of human health, conservation biology, and behavioral science.

The scientists from Zhejiang University, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Northwest University, Yunnan University, Aarhus University, BGI-Research, and other institutes published eight papers in Science today as part of a special research issue. In addition, two papers have been published in Science Advances, and one to be published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Science, Volume 380, Issue 6648, June 2, 2023.

Science, Volume 380, Issue 6648, June 2, 2023.

It all happened long, long ago

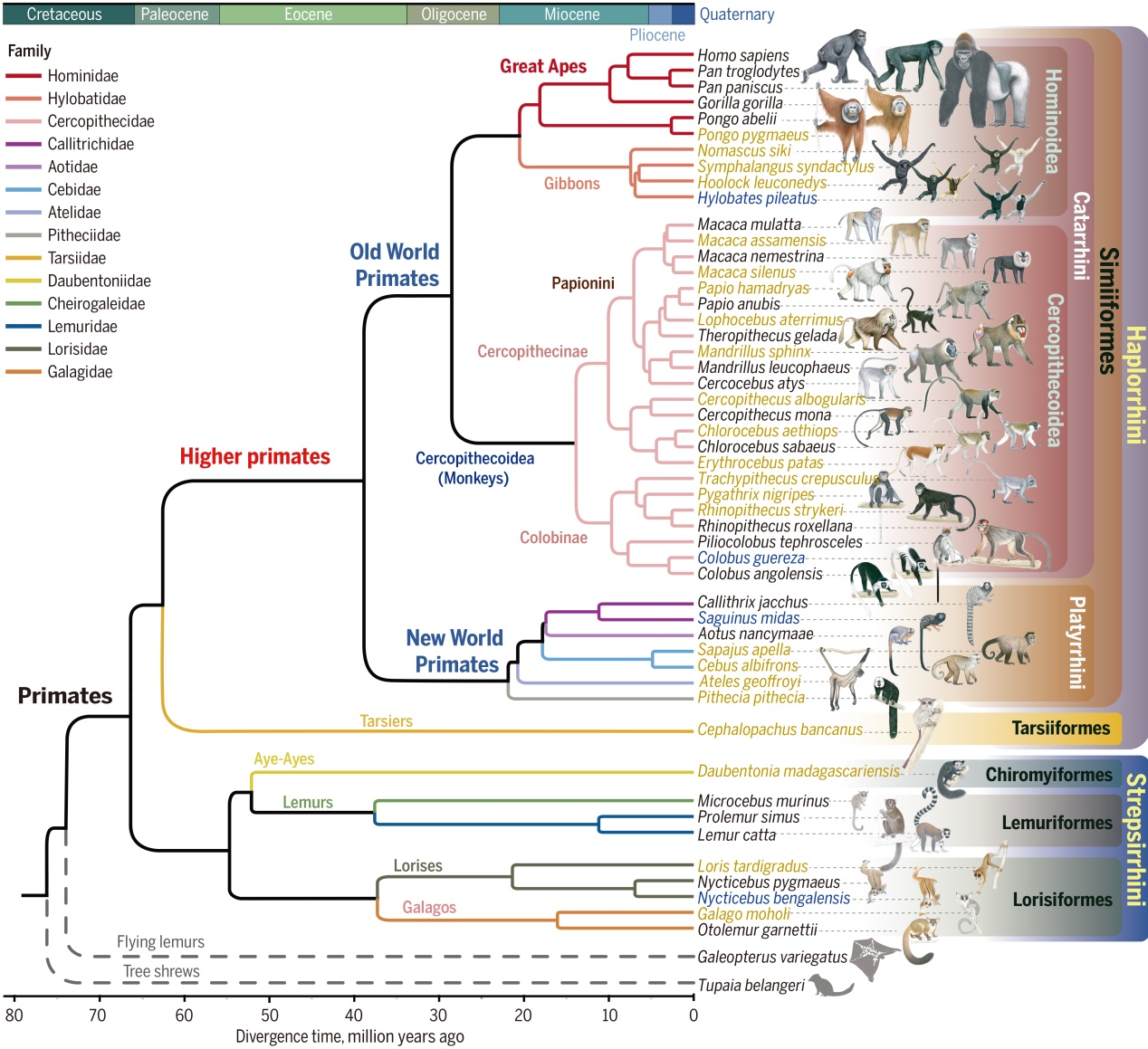

By analyzing genomic and fossil data, the scientists inferred the evolutionary time of each major group of primates and deduced that the most recent common ancestor of all primates likely appeared between 68.29 and 64.95 million years ago. Interestingly, this timeframe aligns closely with the mass extinction event that occurred approximately 65.5 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period. This suggests a potential influence of this major extinction event on the evolution of primate animals.

Furthermore, by analyzing additional chromosomal-level data from Strepsirrhini, a comparatively primitive group of primates, the research has revised the previous hypothesis concerning the origin of human chromosome 8.

Genomic phylogeny of primates. (Credit: Dong-Dong Wu)

Genomic phylogeny of primates. (Credit: Dong-Dong Wu)

Bigger brain and no tail

Throughout their extensive evolutionary history, primate animals have gradually adapted to diverse environments and diets, resulting in the development of unique characteristics such as brain size, skeletal structures, body sizes, and digestive systems.

Relative brain volumes increased during four pivotal periods in primate evolution, particularly after the emergence of great ape species like orangutans. The culmination of this expansion occurred in humans, who possess both the largest brain capacity among primates and the most intricate folding patterns in the cerebral cortex.

The researchers found that some brain-related genes were strengthened during evolution and the larger and more sophisticated primate brains involves a complex interplay of numerous genes and regulatory regions, which continually fine-tune brain development through the regulation of gene expression.

In addition, the research project shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying the formation of forelimbs in primates and the loss of tails in apes, specifically identifying the roles of the NEK1 and KIAA1217 genes. The KIAA1217 gene influences spinal development and its mutation in mice leads to a reduced number of tail vertebrae. The study observed rapid evolution in the regulatory region of this gene among apes, suggesting that mutations in this region may be one of the contributing factors to the disappearance of tails in apes.

Similar DNA doesn’t mean similar relatives

Incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) is a distinctive phenomenon in population genetics where ancestral gene copies do not merge into a common ancestral copy until deeper than previous speciation events. An example of this can be observed in the relationship between humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas. Although humans are more closely related to chimpanzees, the human genome shares over 15% of its genomic regions with gorillas, which is attributed to ILS.

In order to look at ILS in primates, the research team conducted a comprehensive analysis of 29 ancestral nodes using whole-genome data. The study uncovered that ILS was present in 5% to 64% of genomic regions across all evolutionary nodes of primates. This finding highlights the significant impact of ILS on the process of species divergence throughout primate evolution.

Additionally, the researchers devised a novel method to infer species split times. By incorporating the characteristics of ILS in the genome, the researchers were able to estimate the genetic split time of primate species without relying on fossil calibration. Remarkably, the estimated times were consistent with known fossil evidence. This indicates that the analysis of ILS can yield accurate estimations of species split time solely based on genomic data and specific population-related parameters, obviating the need for fossil evidence.

Stay together, stay strong

Gray snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus brelichi). (Credit: Gui-Yun Li)

Gray snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus brelichi). (Credit: Gui-Yun Li)

The research team also delved into the intriguing phenomenon of multilevel society observed in certain primate species, which is relatively uncommon in the animal kingdom. Multilevel society refers to social organizations that exhibit hierarchical levels, such as families, clans, and tribes.

The focus of the study was on the Asian colobine monkey species, which encompasses seven genera, including three genera of leaf-monkeys (Presbytis) and four genera of snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus). The researchers conducted a thorough analysis of the genomes of all seven genera and constructed a reliable phylogenetic tree based on the latest fossil evidence.

The findings of the study challenge the previously held assumption that the ancestors of Asian colobine monkeys entered East Asia from the north. Instead, the research suggests that these monkeys migrated to East Asia and Southeast Asia from the southern foothills of the Himalayas. Furthermore, the study identified cold climate as a significant driving force behind the evolution of multilevel societies in Asian colobine monkeys.

The cold climate likely facilitated metabolic and neurological adaptations in snub-nosed monkeys, leading to enhanced parental care and increased survival rates of offspring. Moreover, these adaptations fostered stronger social cohesion among community members. Such physiological changes provided a solid foundation for the development of larger and more stable social structures in Asian colobine monkeys.

Human beings, as members of the primate order, have long been fascinated by the origin and evolutionary process of primate animals. With over 500 primate species from 16 families and 79 genera, studying this field not only helps us understand the origins of humanity but also revealed the evolutionary history of our unique physical characteristics.

To date, BGI has participated in the research of 84 primate species and has published a total of 67 articles. These achievements have enabled us to answer some of the most compelling questions through genetic research.

Ethical approval was obtained for this research.

For more insights of this inspiring research, please visit the Science Special Issue on Primate Genome: https://www.science.org/toc/science/current