A multi-institutional team led by BGI-Research, Sun Yat-sen University, and others—working across field surveillance, genomics, and infectious-disease ecology — reports in Nature Communications a detailed map of the infectome of small mammals, specifically rats and shrews that often live alongside people in farms, markets, and homes. The study addresses a critical gap in outbreak preparedness: wildlife surveillance has often focused on viruses alone, even though bacteria and parasitic eukaryotes can also cause serious human disease and may spread by very different routes. Treating common small mammals as mobile pathogen reservoirs that move through human environments, the researchers aimed to describe, organ by organ, what these animals carry, where microbes concentrate in the body, and which ecological factors shape spillover risk.

The study “Infectome analysis of small mammals in Southern China reveals pathogen ecology and emerging risks” was published open access in Nature Communications (Published 12 December 2025; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-66462-9).

The study “Infectome analysis of small mammals in Southern China reveals pathogen ecology and emerging risks” was published open access in Nature Communications (Published 12 December 2025; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-66462-9).

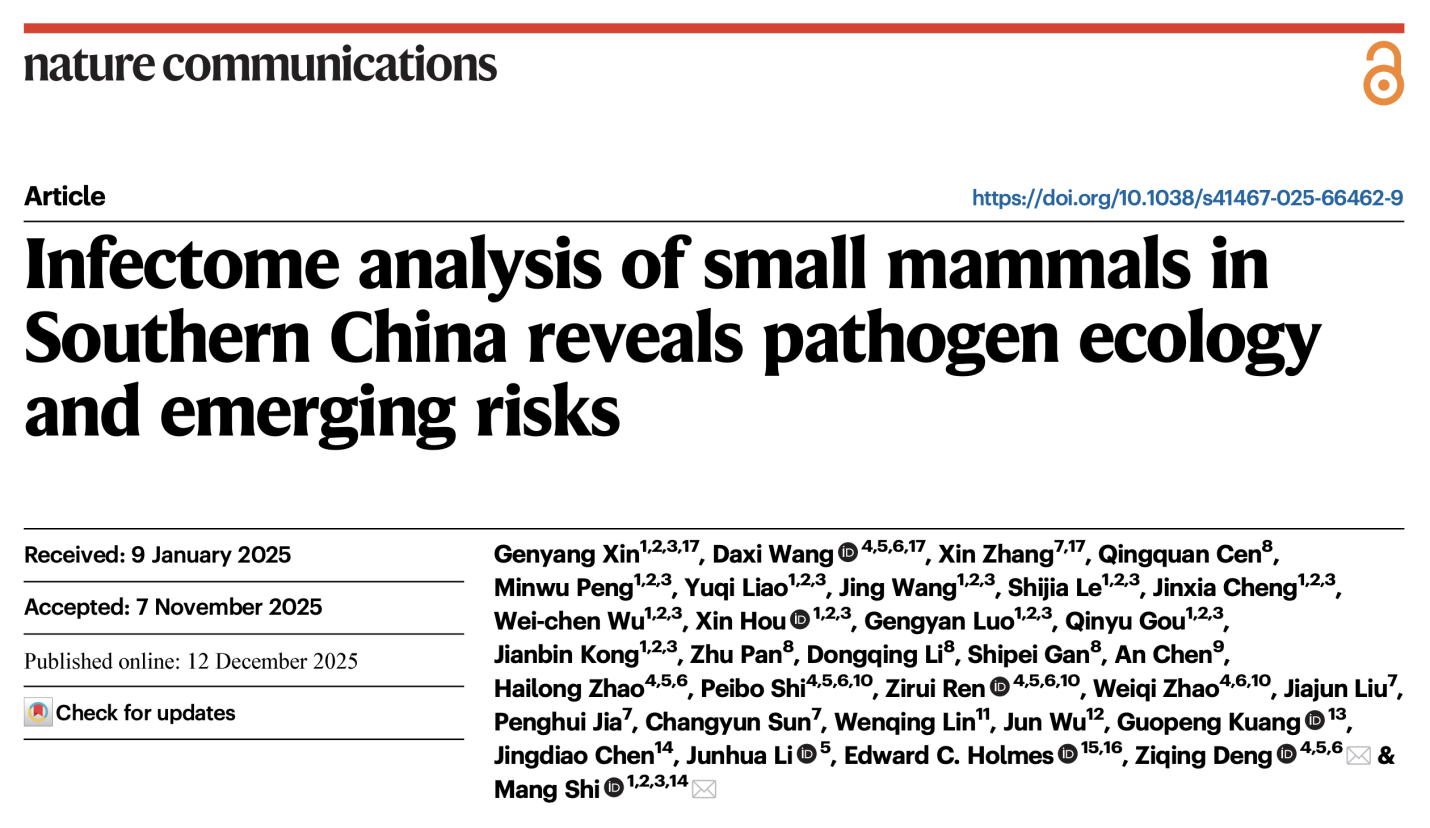

To build that organ-by-organ picture of pathogens, the team sampled 858 individual animals collected across nine regions of Guangdong province during 2021–2022, spanning both residential and agricultural settings relevant to human exposure. Rather than using pooled samples, they sequenced each individual and profiled three tissues per animal: lung, spleen, and gut. These tissues capture microbes linked to respiratory, blood-borne or vector-borne, and fecal–oral transmission pathways. Using metatranscriptomics, they sequenced the total RNA in each tissue as a broad genetic readout of active infections, generating 2,408 separate sequencing libraries and 10.2 terabase pairs (Tbp) of data. Library preparation used the MGIEasy RNA Library Prep Kit, and sequencing was performed on the DNBSEQ T series platform. Pathogen identification was supported by established bioinformatics tools and further validated through phylogenetic analysis of marker genes.

Panels summarise pathogen diversity and positivity across hosts, sites, seasons and tissues — revealing which species, places and sample types carry the highest burden. This identifies surveillance priorities that can be targeted to reduce human exposure risk.

Panels summarise pathogen diversity and positivity across hosts, sites, seasons and tissues — revealing which species, places and sample types carry the highest burden. This identifies surveillance priorities that can be targeted to reduce human exposure risk.

The central finding is a comprehensive inventory of 76 potential pathogen species across major microbial groups: 29 RNA viruses, 12 DNA viruses, five bacteria, and 30 eukaryotic pathogens such as parasites and fungi. Thirty-three of these were newly identified, expanding the known diversity of microbes associated with small mammals in this region. The dataset also detected several known zoonotic agents, including Seoul orthohantavirus, rat hepatitis E virus, Wenzhou mammarenavirus and the rat lungworm Angiostrongylus cantonensis, together with other pathogens of documented or plausible relevance to humans. One notable discovery was a highly divergent orbivirus detected at high abundance in lung and spleen, consistent with a virus that infects mammals rather than an incidental environmental signal.

A key message for public health is that tissue tropism—where microbes reside in the body—can hint at how they spread. The gut carried the highest overall pathogen diversity, especially for RNA viruses and eukaryotic parasites, which aligns with fecal–oral exposure routes through contaminated food, water, or surfaces. The spleen showed lower overall diversity but was enriched for certain DNA viruses and blood-associated bacteria, consistent with systemic or vector linked ecology. The lungs carried the highest burden of eukaryotic pathogens, emphasizing that respiratory tissues can be central not only to viruses but also to parasitic infections and aerosolizable exposure risks in real-world settings.

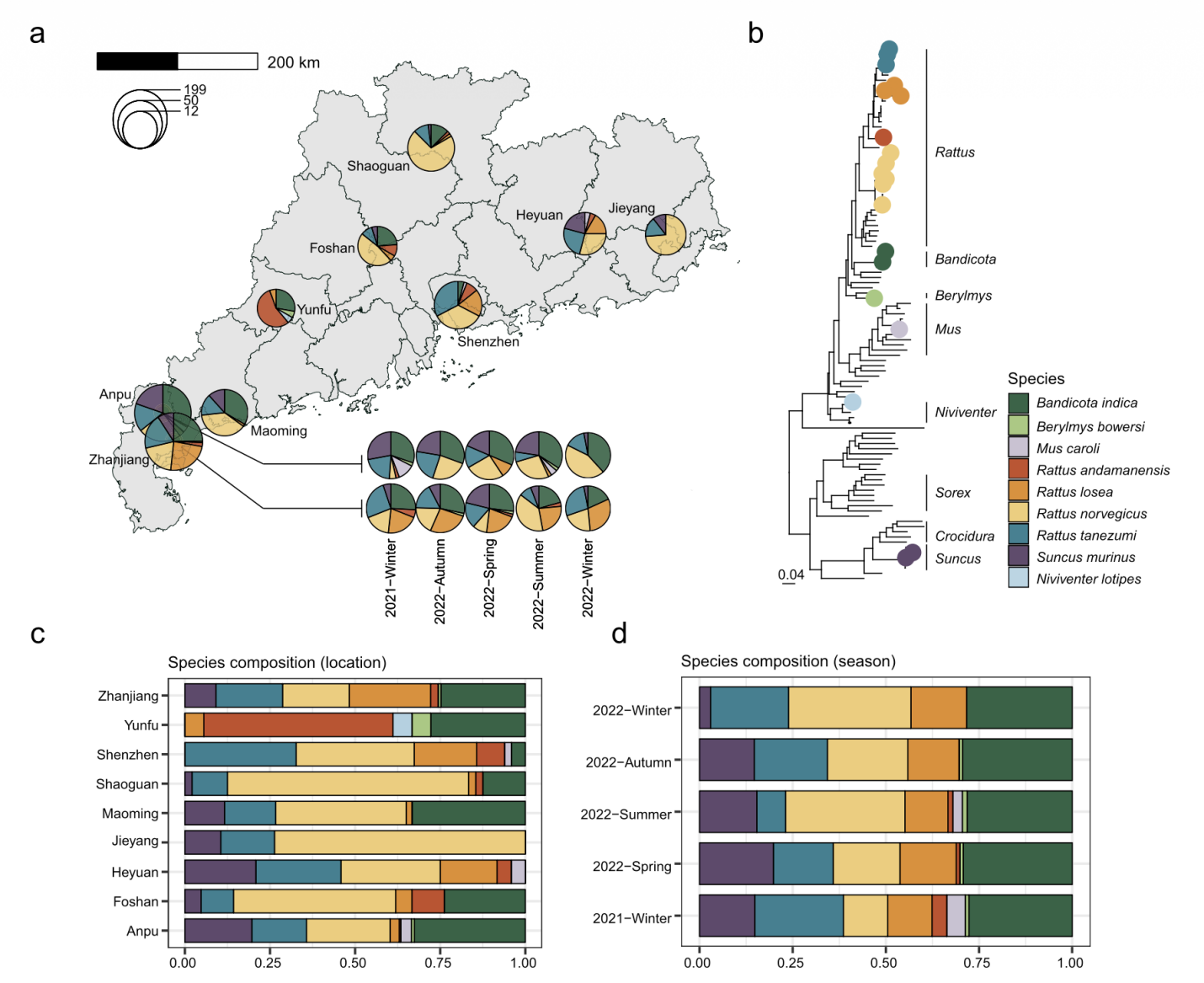

A host and pathogen sharing network reveals key spillover hubs among rodents and shrews; prioritizing surveillance of these species can improve monitoring and reduce human outbreak risk.

A host and pathogen sharing network reveals key spillover hubs among rodents and shrews; prioritizing surveillance of these species can improve monitoring and reduce human outbreak risk.

The work also highlights why spillover preparedness cannot rely on single-pathogen assumptions. Most individual animals carried a median of one detected pathogen across the three tissues, but pathogen sharing across hosts was common. Cross-species transmission appeared frequent, and a subset of pathogens showed evidence of broader host ranges across mammalian groups. In ecological modeling, overall pathogen richness was most strongly associated with geographic region, while the richness of known zoonotic pathogens was more strongly tied to host species, an actionable distinction for surveillance planning. The analysis further points to certain hosts as “hub species” for monitoring, including the bandicoot rat (Bandicota indica) and the brown rat (Rattus norvegicus), which combined broad distribution with higher burdens of human-relevant pathogens in parts of the sampling network.

Beyond the immediate inventory, the broader impact is a reusable framework for early warning. Large-scale, individual-level sequencing that links pathogens to specific hosts, tissues, seasons, and locations can help public-health agencies prioritize where to look, what to test, and when to intensify monitoring, especially in regions where humans and small mammals regularly intersect. The team has made the work broadly accessible through public data deposition and open code, enabling independent reanalysis and international comparison with other wildlife surveillance efforts.

Animal sampling and processing protocols were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University (Approval: SYSU-IACUC-MED-2021-B0123).

This research is available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66462-9